Christianity: Affirming Culture, Denying Culture

During the week, a friend of mine uploaded a screenshot of a Twitter post where the original poster was comparing Mike Bamiloye, a Christian filmmaker with Tunde Kelani, a Yoruba filmmaker. The point of the comparison was how the former undermines the Yoruba culture in his movies while the latter always uphold it.

Many of the early Mike Bamiloye movies tend to follow a storyline where missionaries visit a community given over to idolatry, engage in a face-off with the culture as they seek to bring the gospel to them, and then end up converting the community (or a part of it) as they show the superiority of Christ over the local deities.

The original poster sees this storyline as undermining the Yoruba culture, promoting a foreign religion and culture (the religion of the whites) over our own indigenous religion and culture. This trend – castigating Christianity (and Islam) as a foreign religious imposition and fighting for the honour of one or more African traditional religions – has now become common in certain circles as part of a nationalistic or pan-African bent.

My aim in this article is to argue that Christianity has always been willing to preserve and honour cultural elements that do not undermine its message. And when it does discard certain cultural elements that subvert its message, it has been right to do so. In arguing these points, I will also point out that the reduction of Christianity to a white man’s religion (often a synonym for “Western religion”) does not do justice to the inherent universalising tendency of the faith.

A global church with a global mission

When Jesus rose from the dead, he gave his apostles a commission to spread the gospel to all the nations (Matthew 28:18-20). They were to begin from Jerusalem, move to Judea, Samaria, and then the very ends of the earth (Acts 1:8).

This global or universal mission was rooted in the nature of the gospel itself – Jesus came to take away the sin of the world (John 1:29). Said differently, “For God so loved the world, that he gave his only Son” (John 3:16). If Jesus is the saviour of the world, then the gospel is the power of God unto salvation to both Jews and Gentiles (Romans 1:16). Moreover, Peter insists in one of his sermons that salvation can come from no other name except the name

of Jesus Christ (Acts 4:12).

If Christ came to save the world, then the message of his salvation had to go to the whole world, hence the universal nature of the gospel. And if the success of the gospel is guaranteed by God’s own sovereignty, then the church – the people who respond to the gospel – will be universal.

Consequently, it should not be strange that Christianity is a missional religion. We believe that we have a message that is essential to the salvation of humanity and we are therefore bound to bring that message to the entire world. As Paul said, “Woe to me if I do not preach the gospel!” (1 Corinthians 9:16).

Is Christianity a Western religion?

Christianity cannot be a Western religion in its origin since Christ and his apostles were Jews who lived in Palestine. In fact, the gospel message moved just as Christ said – Jerusalem to Judea to Samaria and then the ends of the earth.

Paul was the apostle who really took Christianity to the Gentile territories. He established churches in Asia Minor (Turkey) and many Greek cities.

Though Paul did not establish the church in Rome, he was in Rome himself and also wrote a letter to the City that has become foundational in Christian theology. Christianity was a persecuted religion in the Roman Empire before Constantine converted and made it the official religion of the empire.

While the focus has always been on Rome as the capital of the empire, Christianity continued to thrive in many places outside of Rome.

The gospel entered Egypt early and Alexandria had become an important Christian center in the second century with important church fathers like Clement and Origen ministering there. From Egypt, the gospel spread across to North Africa where one of its most profound theologians – Augustine of Hippo – ministered. And by the fourth century, there was already a church in Ethiopia, East Africa.

Even before the conversion of Constantine, there was a Christian kingdom in Edessa and Armenia. And, according to James Stamoolis, “The church certainly was in India in the first centuries of the Christian era.”[1]

Christianity was also thriving in the eastern part of the empire even though the theological (and non-theological) disputes between the East and the West continued to cast a shadow on the church’s unity till the eventual Great Divorce of 1054. But the Eastern (Orthodox) churches continue to exist in Eastern Europe.

While this does not deny the fact that Christianity prospered the most in the West (especially with the papacy growing in power in the medieval period), it shows that Christianity is not a Western religion in origin or in mission.

Christianity in Africa

This is the way Wikipedia summarised the journey of Christianity in Africa between 500 and 600 AD:

“Christianity in Africa first arrived in Egypt in approximately 50 AD. By the end of the 2nd century, it had reached the region around Carthage. In the 4th century, the Aksumite empire in modern-day Ethiopia and Eritrea became one of the first regions in the world to adopt Christianity as its official religion. The Nubian kingdoms of Nobatia, Makuria and Alodia followed two centuries later. Important Africans who influenced the early development of Christianity include Tertullian, Perpetua, Felicity, Clement of Alexandria, Origen of Alexandria, Cyprian, Athanasius and Augustine of Hippo.”

The church is a global body with a global mission and it did not need to wait until the transatlantic slave trade to enter Africa. The urgency of the gospel commission already pushed it to Africa in its first 500 years of existence.

Africa did not just produce great theologians during this time; according to Timothy Yates, Egypt “provided the seeds of monasticism, a movement of great importance for the church of the future.”[2] This is why the attempt to reduce Christian interest in Africa to the colonial impulse of Western powers is wrong-headed.

Of course, the imperial pursuits of Western European powers provided the context where many African countries, including Nigeria, encountered Christianity in the 18th and 19th centuries. Yet, it’s impossible to reduce the missionary efforts in these years to mere political machinations.

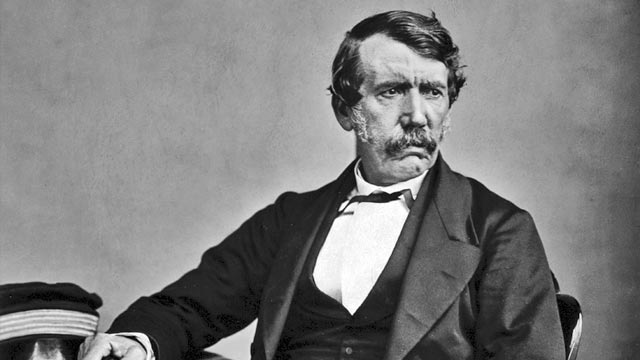

People like David Livingstone were urged on to Africa by a desire to bring the gospel to places where it was not known and to put an end to the transatlantic slave trade (contrary to the interests of some Europeans). In fact, it was this anti-slavery momentum that led to the founding of Freetown in Sierra Leone which became “an outpost for the spread of the gospel” and inspired Christian communities in Abeokuta and Badagry.[3]

Christianity and culture

The relationship between Christianity and culture is not as straightforward as detractors often make it sound.

Christianity is both culture-affirming and culture-denying.

Culture affirming

Christianity is culture-affirming because it believes that grace does not destroy nature.

God created this world and ordered it according to his own principles. There is a natural order that is inherent in creation as everything God has made moves towards its end/goal/purpose (or final cause, as Aristotle puts it).

Christianity does not upturn this natural order. Men and women marry and give birth, human beings are social creatures that bond together in communities, in these communities, they order their activities through a form of government, and humans also come together to exercise dominion over nature to improve their welfare. All of these are part of the natural order (people without the gospel know them and act accordingly) and grace does not destroy it.

As Stephen Wolfe puts it, “Grace does not destroy, abrogate, supersede, or undermine nature but rather affirms and completes it.”[4] Herman Bavinck agrees: “The reality of the incarnation militates against any nature/grace dualism; the gospel is not hostile to the world as creation but to the world under dominion of sin.”[5]

Affirming natural law

One of the aspects of the natural order that grace affirms is natural law. In Romans 2, Paul taught that the law of God is written on the hearts of Gentiles who do not have the Torah that the Jews had (verse 14). Therefore, they often do what the law requires while Jews who have an external law don’t (verses 12-13).

This shows then that many pagan nations who have not heard the gospel have moral codes that are affirmed (not destroyed) in the Scriptures. It’s no surprise then that many find similarities between the Code of Hammurabi and the Torah. Grace does not destroy nature.

As C.S Lewis said, “If anyone will take trouble to compare the moral teaching of, say, the ancient Egyptians, Babylonians, Hindus, Chinese, Greeks and Romans, what will really strike him will be how very like they are to each other and to our own.”[6] There is a universal natural law, what Lewis calls the law of nature, that seems to pervade every civilisation.

We see an example of this in Paul’s letter to Corinth. When a man was sleeping with his father’s wife, Paul rebuked the church for not firmly dealing with the issue. Here is how he described this sin: “of a kind that is not tolerated even among pagans.” Though the pagans have some bad laws (more on that later), Paul was willing to admit that they had good ones too.

Affirming natural theology

This dictum (grace does not destroy nature) also applies in the intellectual realm (in what is called natural theology). There is a knowledge of God that is common to every man. Paul affirmed that God has revealed himself to everyone in nature (Romans 1:16-23) and in conscience. According to John Calvin, there is a “sensus divinitatis” (sense of the divine) that is common to us all which “in a wide variety of circumstances produces in us beliefs about God.”[7]

It is not therefore surprising that where appropriate, Christian theologians often used terms and concepts developed in Greek philosophy to explain the Christian faith. According to David Haines, the great patristic theologians such as Augustine, Gregory of Nyssa and Basil of Caesarea affirmed that “all truth is God’s truth, regardless of where it is found.”[8] Consequently, they were willing to affirm Greek philosophy where it was in line with the Scriptures. In fact, according to James Stamoolis, theologians in Alexandria recognised Greek philosophy as a “preparation for the gospel.”[9]

We see Paul doing something similar when he quoted a pagan poet to make his point that we depend on God for our existence and sustenance (Acts 17:28). In this same chapter, he acknowledged the presence of the sensus divinitatis in the Athenians as they built a temple to the unknown God.

A global (and diverse) church

We also see cultural affirmation in the diversity of the Christian church. As we saw earlier, Christianity is by nature a global phenomenon. In Revelation 5:9, we see that God ransoms people from every tribe, language, people, and nation. Even in the new Jerusalem, we will not be a monolithic whole; John saw that the glory and the honour of the nations will be brought into the city (Revelation 21:26).

Commenting on Rev. 21:26, Bavinck notes that “tribes, peoples, and nations all make their own particular contributions to the enrichment of life in the new Jerusalem.” “The great diversity that exists among people in all sorts of ways is not destroyed in eternity,” he continued, “but is cleansed from all that is sinful and made serviceable to fellowship with God and each other.”[10]

This diversity is inherent in the global church. While we are united by word and sacraments, no one can say that a church in the US is a mere carbon copy of a church in Nigeria, and vice versa. While there are unifying elements, there are also cultural differences – clothing, music, language, etc.

Contrary to the inveighing of nationalists type, Western believers don’t typically try to create Nigerian churches in their image. There is room for local cultural expression as long as there is no compromise of Christian doctrine and ethics.

In fact, many “battles” were fought among believers to adapt Christian worship to the local population – translation of the Bible to local languages and the use of local language in worship.

And those of us who have been given the grace to be part of a global church know firsthand how Christianity has respected the diversity of cultural and local expressions, anchored in the unity of Christian theology and ethics.

We see an example of this in the New Testament. Paul insisted that Corinthian women cover their heads as a local expression of the woman’s submission to her husband (1 Corinthians 11). He also instructed many churches to greet each other with a holy kiss (2 Corinthians 13:12, Romans 16:16), a cultural practice that is not appropriate in some local contexts.

Culture denying

Nevertheless, Christianity is also culture-denying.

Nature is still good but it is infected with sin. And while grace does not destroy nature, it saves it, thus elevating and perfecting it. This balance was especially struck in the Reformation, according to Bavinck. “The Reformation sought a Christianity that was hostile, not to nature but only to sin, and had a reforming and sanctifying effect upon natural life as a whole, including the world of culture, society, and politics.”[11]

Moral denial

While natural law still exists, it has been corrupted by sin. Therefore, many nations, without knowledge of the Scriptures, will affirm laws and moral practices that are contrary to God’s law.

Christians will reject these laws and moral practices because while grace does not destroy nature, it perfects it. In the Roman Empire, Christians stood against temple prostitution and fornication. In the 19th century, they stood against slavery and the trans-Atlantic slave trade.

Christian missionaries also stood against human sacrifice, the live burial of slaves to accompany dead kings, and the killing of twins in Nigeria. (They also worked to bring education, good health, and vocational skills to the locals).

It is worth noting that the missionaries were not against all these practices because they were African but because they were considered contrary to natural law (divorced from sin) and human dignity. It is no wonder then that when Western Christians became embroiled in the anti-natural law practice of homosexuality, it is Christians from the Global South who have been taking a stand against the craziness (an example is GAFCON’s rejection of the Church of England’s decision to bless same-sex marriage).

Intellectual denial

While Christian theologians found Plato and Aristotle useful, they knew that the God revealed in the Scriptures is more than the One-Good of the former and the unmoved mover of the latter. They were willing to reject aspects of Platonism and Aristotelianism that were contrary to the Scriptures as well as outrightly deny Greek philosophies like Gnosticism.

In Acts 17, we see how Paul could affirm the statement of the Athenian poet while rejecting their polytheism and encouraging them to worship the only true God that has revealed himself in Christ.

Since then, Christians have rejected polytheism and other forms of monotheism that do not recognise Christ as God-incarnate. Western philosophies like pantheism, panentheism, Darwinism, and Deism were rejected.

Beyond philosophies, we see how in Acts 18, many Ephesians “who had practiced magic arts brought their books together and burned them in the sight of all” (verse 19) and how the believers in the city had to turn away from Artemis to embrace the living God.

Whether in Greece, Asia Minor, or Rome, the Christian message consistently required that people let go of the gods of their cultures and traditions and embrace the only living God who has been revealed in Christ.

Therefore, when missionaries rejected African Traditional Religion, it was not because they were just anti-Africa. In ATR, “mediation between God and humans is the chief religious role of the minor deities,” according to Tite Tienou. “They share this role with the ancestors, the elders, and the various religious functionaries of African societies.”[12]

Christianity had to reject this metaphysics because “there is one God, and there is one mediator between God and men, the man Christ Jesus, who gave himself as a ransom for all” (1 Timothy 2:5-6).

So, though Romans 1 affirms that God has revealed himself to everyone, it goes on to say that we have exchanged the truth of God for a lie by worshipping created things rather than the creator (verses 21-25). We have set up idols that are the creation of our own hands and called them gods (Isaiah 44:9-20).

The Christian response is that “an idol has no real existence” and that “there is no God but one” (1 Corinthians 8:3). What pagans sacrifice, they sacrifice only to demons (1Corinthians 10:20), and in their feasts, they commune with these demons.

This is why Christianity rejected all idols and offered a metaphysics where the triune God who created the universe, transcends the universe he created, and is also immanent in creation, is the only one worthy of worship and adoration.

Cultural practice denial

While the diversity of local expressions was permitted, this permission was still subject to Christian ethics. For example, the missionaries did not encourage polygamy which was an acceptable practice among natives. This was not a product of the westernisation of the faith but Jesus’ insistence that monogamy is the creation order.

Of course, there is no denying that the missionaries may have attempted reforms too quickly or indulged in them in the wrong spirit, but the very idea of culture denial is intrinsic to Christianity.

Again, this was not an anti-African agenda. Christians in Rome rejected its imperial cult and patronage system.

Should metaphysics be relativistic?

When people complain about Christianity being the white man’s religion, the first question I ask is why they don’t extend it to science, technology, and something like republicanism.

Most of the scientific theories we teach in our schools don’t originate from Africa. It’s the same when we enter our social science departments. Most of the foundational economic ideas that have led to prosperity across the globe were propounded by Englishmen and Scots.

Or take technology. How many of the technological innovations that have made our lives easier compared to our forefathers have come from Africa?

What about the republicanism that many of us now practice? Did it originate with us?

When are we going to start railing against Western science, technology, and social science?

What makes this more interesting is the Christian influence behind all these things we don’t want to throw away.

Regarding science (which then led to technological innovations), Stephen Meyer notes that “belief in a God – and Christianity specifically – played a decisive role in the rise of modern science during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.”[13]

In the same way, republicanism has its roots in the Puritans that left England to settle in what is now known as America. Religious liberty, limited government, and natural rights are ideas that were hashed based on Christian principles. [14]

So, why do we want to reject Christianity just because it came from the West and disrupted some of our practices and theology? Didn’t science, technology, capitalism, and the social sciences disrupt some of our practices and theology?

I think the problem is an embrace of relativism in moral and spiritual matters that is not extended to science (natural and social). In the case of the latter, we want to find the truth but for the former, we believe everyone should believe what they want and behave as they want.

But relativism is self-defeating. If relativism is absolutely true then at least one absolute truth already exists. But if relativism is not absolutely true, then why bother with what it says?

Just as we seek the truth in science, we should seek it also in metaphysics and theology. There is either one God or there are many gods. God is either absolute unity or trinity. Our local deities are either the mediators between God and men or Jesus is. Our idols are either nothing or something.

If someone believes that Christianity’s answers to metaphysical questions are true and those of his forefathers are wrong, then a commitment to the truth requires him to cling to Christianity just as the pursuit of truth led him to embrace Einstein and the others.

If our forefathers could be wrong in other aspects, then their metaphysics can be wrong as well. We owe it to them to find the truth and embrace it even if that truth comes from a religion that originated in Palestine and was brought to our shores from England.

Suppose a man was drowning and a foreigner threw him a life jacket. Would it be smart for him to reject it because he didn’t know the man or because the life jacket was made in China instead of the local store?

In the same way, if the Christian message of salvation is true, it will be foolhardy to reject it because it didn’t come from our forefathers or because it took away some of their cultural expressions. The more important question then is if Christianity is true.

Once we disabuse our minds of relativism, then the whole nationalist and pan-African antipathy towards Christianity will lose its reasonableness.

Since Christian ethics flows from its metaphysics, then accepting Christian ethics makes sense for the person who has accepted its metaphysics and theology more broadly.

In summary, where truths come from should not matter. To avoid the genetic fallacy, we must focus on the content of propositions and worldviews rather than discard them based on where they come from.

We cannot accuse Westerners of cultural superiority and then also practise the same when we insist that whatever is African must be true, beautiful, and good. Humility requires that every culture keeps interacting with the aim to come to a better knowledge of what is true, good, and beautiful. This will mean that sometimes we insist on our cultural heritage as the truth and sometimes we yield to other cultures understanding.

Conclusion

Christianity does not have any issue with indigenous cultural practices, beliefs, and expressions except when they have been tainted with sin, in which case grace perfects nature. Otherwise, its commitment to natural law, natural theology, and a global (diverse) church leads it to embrace them.

When Mike Bamiloye shows the superior power of Christ over local deities or Christian denial of immoral cultural practices, that does not represent a wholesale rejection of a particular culture. He can embrace and appreciate all the things in that culture that are not contrary to grace (e.g., the demand for respect for elders and an emphasis on community).

More importantly, he can celebrate aspects of that culture while at the same time insisting that Christianity got it right (that Jesus indeed is the Christ) and his forefathers got it wrong (there is only one God and there is only one mediator between him and men). He can embrace Christ as the way, the truth, and the life irrespective of where that knowledge came from.

Finally, Christianity is a global movement because the gospel is for the whole world. The message that salvation can be found only in Christ must penetrate every culture and society. If there is any religion that cannot be reduced to a mere cultural phenomenon, it’s Christianity. Christ is the light of the world and we will continue to shine his light until the whole earth is filled with the knowledge of the glory of the Lord (Isaiah 6:3).

Footnotes

[1] David Horton (ed.), The Portable Seminary (Plateau state: African Christian Textbooks, 2014), p. 558.

[2] Ibid, 439

[3] Ibid, 520

[4] Stephen Wolfe, The Case for Christian Nationalism (Idaho: Canon Press, 2022), p. 23, Kindle.

[5] Herman Bavinck, Reformed Dogmatics, Abridged in one volume (Grand Rapids: Baker Publishing, 2011), p.82

[6] C.S Lewis, Mere Christianity (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2021), p. 24, Scribd.

[7] Alvin Plantinga, Knowledge and Christian Belief (Grand Rapids, William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2015), p. 65, Scribd.

[8] David Haines, Natural Theology (North Carolina, Davenant Press, 2021), p. 177, Kindle.

[9] David Horton, Portable Seminary, 558.

[10] Bavinck, Reformed Dogmatics, 775.

[11] Bavinck, Reformed Dogmatics, 83.

[12] David Horton, Portable Seminary, 405.

[13] Stephen Meyer, Return of the God Hypothesis (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2021), p.28, Kindle.

[14] See Glenn Sunshine, Slaying Leviathan