Any glance through his epistles makes it obvious that one of Paul’s overwhelming desires is for the churches to be united. Phrases like “one mind,” “one voice,” “one purpose,” “be like-minded,” and “same attitude of mind,” among others, are scattered throughout his writings.

Here is one example: “Therefore if you have any encouragement from being united with Christ, if any comfort from his love, if any common sharing in the Spirit, if any tenderness and compassion, then make my joy complete by being like-minded, having the same love, being one in spirit and of one mind” (Philippians 2:2,3).

Yet, theological disagreements remain within the universal church and its local manifestations. It’s almost impossible to find two random Christians who agree on all points of theology.

Navigating the reality of theological differences and the ideal of unity of mind has always proved difficult.

[For more on what it means for the church to be united and pursue unity, read “The Church as a Witness to God’s Reconciling Power”]

I was reminded of this difficulty during a recent scuffle on Nigerian Christian Twitter. A clip of a popular pastor teaching what many considered theologically inaccurate went viral, and some Christians responded by calling out the error.

This led to a flurry of opinions about the appropriateness of the responses. For some, it was against the spirit of Christian unity that requires that we be of one mind instead of washing our dirty linen in a space shared with unbelievers. Others were indifferent about the theological controversy and showed greater concern with the tone of voice and the labelling of people as heretics or fake pastors.

But does this concern for unity and tone of voice mean that we can sit by and allow the gospel to be distorted or corrupted, all in the name of unity?

This has always been the paradox of unity and theological integrity. And anyone with the faintest knowledge of Christian theology knows that paradoxes like this abound.

Interestingly, theological disagreements are as old as the church. Thus, reflecting on how people navigated this paradox in the NT can shed some light on our path today.

Public disagreement is not inherently wrong

In Galatians 2, we have a record of Paul’s public confrontation with Peter on the issue of the relationship between Jews and Gentiles in the church.

Peter was on the same page as Paul regarding the full inclusion of Gentiles in the church. In verse 14, Paul made the point that Peter, though a Jew, was already living like a Gentile, which most likely refers to him eating meals with Gentiles (verse 12), an acknowledgment of the irrelevance of the Jewish food laws in the gospel dispensation (see Acts 10:15, 34-35).

However, when certain men came from James (the Jerusalem church), he began to separate himself from the Gentiles, which likely refers to his refusing to eat at the same table with them. Robert Gundry, a New Testament scholar, suggests two reasons why Peter acted this way: fear that “eating with Gentile Christians would make it difficult to convert other Jews,” or fear of “further persecution by Jews who considered a Jewish Christianity wide open to Gentiles a threat to Judaism.”[1]

Whatever might have been the motivation, Paul did not hesitate to publicly confront Peter (despite his position in the church) about his hypocrisy. Peter’s actions had negatively influenced other Jewish Christians, including Barnabas, and it was before them all that the sharp rebuke came. In essence, all those who saw Peter’s hypocrisy also heard the rebuke.

“I have no doubt that he did talk to Peter privately,” said Don Carson, a New Testament theologian. “He’s just the sort of man who would. I just cannot imagine that this blew up overnight, and then Paul made a federal case without talking to the man. But obviously, he hadn’t convinced him. Peter still does his own thing. The issue, from Paul’s point of view, is so serious and, because Peter’s action is public, Paul’s rebuke must also be public.”[2]

In essence, Carson envisions a process like that of Matthew 18. There, Jesus taught that believers should first try and settle their disputes privately. When it remains unresolved, they should invite two or three people who will act as arbiters. If this fails, then the matter must go before the church. In this ideal scenario, there is progression from the private to the public.

Though there is nothing in the text that shows that this was the process Paul followed, we at least know from this text that public confrontation is not inherently wrong. We also see that there is nothing wrong with ensuring that all those who are influenced by an error (spoken or acted) also get to hear the correction of the error.

Not everything is heresy

One of the problems with handling theological disagreements among believers is that every doctrine is treated as a theological essential, such that if someone disagrees with a particular view, then they must be a heretic. For example, some Charismatics will consider non-Charismatics (who don’t believe that tongues is the evidence of Spirit baptism, for example) as heretics, and vice versa.

However, this is not how the Christian church has used the word “heresy.” “Heresy is a judgment that a certain set of ideas pose a threat to the community of faith,” according to Alister McGrath, a theologian and historian. It is “a form of the faith that is held ultimately to be subversive or destructive.”[3]

Heresies are contrasted with orthodoxy, which represents the accepted views of the Christian church. “In the second century, the binary opposition ‘heresy-orthodoxy’ began to emerge as a way of excluding certain groups and individuals from the Christian church,” noted McGrath. “Hairesis (Greek) now meant a school of thought that developed ideas that were subversive of the Christian faith, which was to be opposed to orthodoxia (Greek)—an authentic and normative version of the Christian faith.”

In historical theology, heresies are usually defined as unorthodox views that the church fought against in the first five centuries of its existence. These are typically unorthodox views about God, Jesus Christ, and the Holy Spirit.

The orthodox views about these issues are summarized in the Apostle’s Creed, the Athanasian Creed, and the Nicene Creed. These creeds represent the attempt of the early church to accurately outline the essentials of the Christian faith.

Though other disputes remained (regarding the appropriate day for Easter, for example), these were not seen as sufficient to define what is orthodox and heretical.

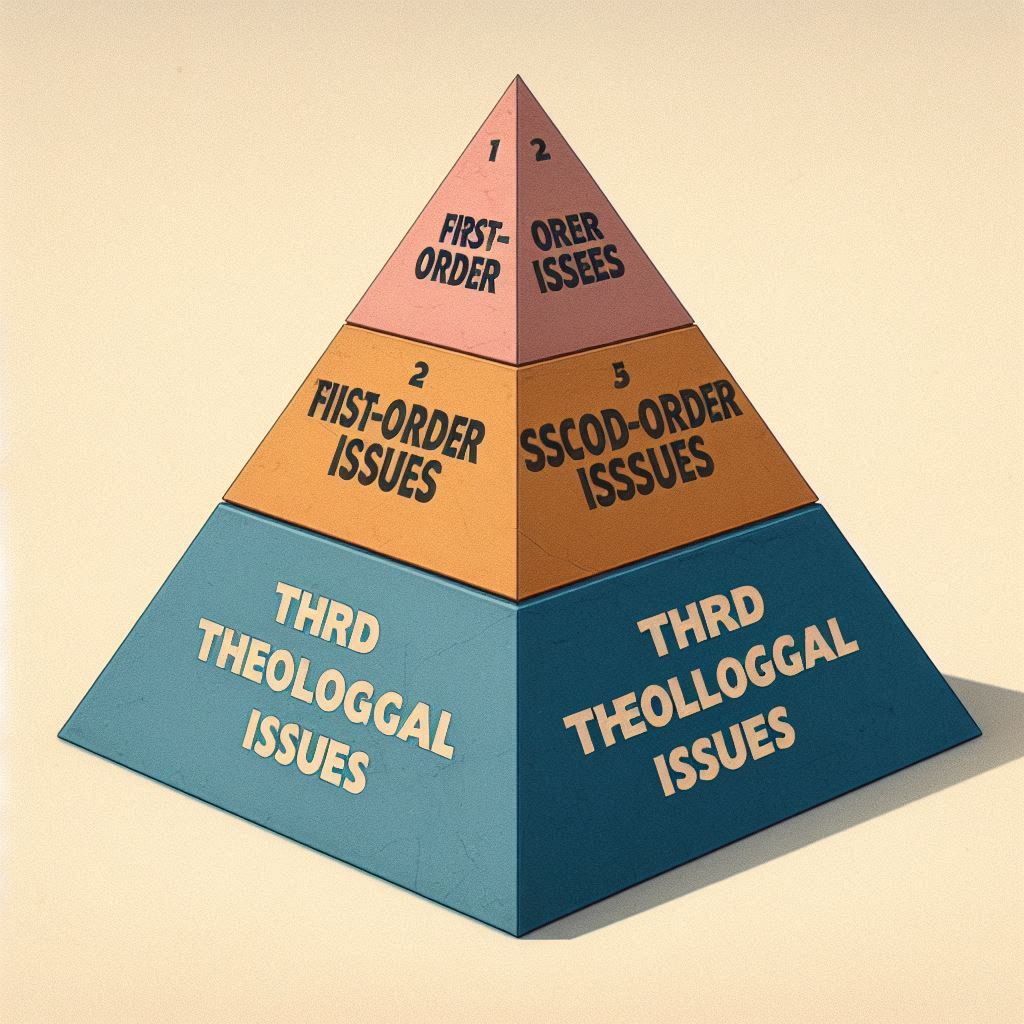

Concerning this, Albert Mohler, the President of the Southern Baptist Convention, introduced the term “theological triage” to the world of Christian theology to reflect the need to rank theological issues in an order of importance.

“Today’s Christian faces the daunting task of strategizing which Christian doctrines and theological issues are to be given highest priority in terms of our contemporary context,” he said. “This applies both to the public defense of Christianity in the face of the secular challenge and the internal responsibility of dealing with doctrinal disagreements. Neither is an easy task, but theological seriousness and maturity demand that we consider doctrinal issues in terms of their relative importance.”[4]

Mohler proposed three levels of theological urgency:

- First-level theological issues (denial of these doctrines constitutes a denial of the Christian faith): The Trinity, the full deity and humanity of Jesus Christ, justification by faith, and the authority of Scripture.

- Second-level theological issues (different views result in significant boundaries usually along denominational lines): The meaning and mode of baptism, and women’s ordination are examples.

- Third-level theological issues (people with different views can remain in close fellowship in the same denomination and local congregation): Eschatology and different interpretations of some difficult texts that do not bear directly on first-level and second-level issues.

While there is nothing sacrosanct about Mohler’s construction, the idea of theological triage itself helps us to handle the paradox of unity and faithfulness to scriptures.

By understanding what the first-level theological issues are, we can avoid calling people heretics or fake pastors over every point of disagreement. We can recognize essential doctrines, the denial of which will constitute a denial of the faith, and differentiate them from those doctrines over which we can disagree while still recognizing that we are brothers and sisters in the faith.

This approach is common in other intellectual fields. Empiricists like Locke, Berkeley, Hume, Bacon, and Hobbes had sufficient agreements that justify putting them under one umbrella, but also enough disagreements to avoid equating their philosophical systems. Political conservatives agree on certain fundamentals, yet disagreements abound.

But does this not mean that certain truths are unimportant?

Well, does the doctor’s choice to attend to an accident victim over someone with a migraine headache mean that the migraine headache is unimportant?

Not at all!

“A structure of theological triage does not imply that Christians may take any biblical truth with less than full seriousness,” said Mohler. “We are charged to embrace and to teach the comprehensive truthfulness of the Christian faith as revealed in the Holy Scriptures. There are no insignificant doctrines revealed in the Bible, but there is an essential foundation of truth that undergirds the entire system of biblical truth.”

Is public confrontation always necessary?

This distinction also helps us gain some clarity regarding Paul’s confrontation with Peter.

Paul’s issue with Peter (and those he influenced) was that they were not acting in line with the truth of the gospel. This was a big deal for him. Though Peter held the same view as Paul, he was denying that truth by his action (which is why Paul called him a hypocrite). This confusion can lead others to hold wrong views about the gospel. As they say, “actions speak louder than words.”

Given that the gospel was at stake, Paul had to take a hard line and publicly confront a fellow apostle.

“Where the heart of the gospel is at stake, nothing is more important,” said Carson. “If that means that Christians get persecuted for it (Carson takes the second view proposed by Gundry above), then we get persecuted for it. If it means that sometimes one Christian who has this more sorted out than others has to rebuke another, well, so be it. But this is too important.”

Therefore, a premillennial using Paul’s action on a matter crucial to the clarity of the gospel to justify calling out an amillennial on social media will be misunderstanding the whole point of Galatians 2 and the concept of theological triage.

Of course, two equal and opposite errors can result from this. First, a lack of courage and a tendency to agreeableness can make us narrow the scope of what the fundamental truths of the faith are. Second, pride and a tendency to divisiveness can make us widen the scope of what the fundamental truths of the faith are.

This is why we must constantly keep a watch over our hearts and keep asking if it’s God’s glory we are seeking or ours.

Heresy and false teachings exist

Paul surely disagrees with those who think nothing is ever a heresy and that we can always agree to disagree.

In Galatians 1, he left the kid’s gloves at home when he placed a curse on those who distort the gospel by preaching a gospel that is different from the one he preached to the church (verses 6-10). He was also confident that those troubling the church with false gospels will suffer God’s judgment (Galatians 5:10).

Paul also called out those who teach the doctrines of demons (1 Timothy 4:1-3), deny physical resurrection (2 Timothy 2:18), oppose the truth (2 Timothy 3:7-8), cater to the sensual desires of their audience (2 Timothy 4:3), cause divisions with their false teachings (Romans 16:17), and deceive people for material gain (Titus 1.10,11; 2 Corinthians 2:17).

Furthermore, Peter warned the church against false teachers who introduce destructive heresies, deny Christ, lead people to immorality, and exploit them for financial gain (2 Peter 2:1-3). John also mentioned deceivers who refuse to acknowledge Jesus’ humanity (2 John 1:7), and Jude wrote about those who turn the grace of God into a license for immorality (Jude 4).

New Testament writers even go as far as asking the church to ignore these false teachers (2 Timothy 3:5, 2 John 1:10, Romans 16:17, 2 Timothy 3:5, Titus 3:10). You can count on it that some sensitive souls called the apostles divisive.

All of these show that the concerns of the NT authors even extended beyond what historical theology categorizes as heresies (false teachings about God, Jesus, and the Holy Spirit) to include false teachings that promote immorality and sensuality in a bid to make money. All of the latter will apply under the category of “distortions of the gospel,” which is what Paul was concerned about in Galatians.

We can conclude then that church leaders must warn their members against heresies and false teachings as well as heretics and false teachers. In some cases, this may even require name-dropping (1 Timothy 1:19-20, 2 Timothy 1:15, 2:17; 3 John 9), and some sensitive souls may feel offended (God bless their souls).

However, John Piper, a retired pastor and theologian, suggests that church leaders should consider these five factors before deciding to name-call false teachers[5]:

- The seriousness and deceitfulness of the error

- The size of the audience

- Whether it is a one-off error or a consistent one.

- The vulnerability of your church members to that false teacher

- Your role in influencing other shepherds.

Even then, the focus should be on the teaching rather than the name. “When you do name a false teacher, it’s best to do it in a setting where you do more than name-drop,” said Piper. “You explain the error, you give reasons for rejecting it, you communicate complexities, you set a tone of longing for truth and love — you’re not just slinging mud.”

“Everyone I don’t like is a heretic.”

However, as we have said above, not every disagreement requires the heretic or false teacher label.

Moreover, it seems that Paul refused to attach the false teacher label to those who preach the true gospel out of wrong or false motives. We see this in his letter to the Philippians:

“It is true that some preach Christ out of envy and rivalry, but others out of goodwill. The latter do so out of love, knowing that I am put here for the defense of the gospel. The former preach Christ out of selfish ambition, not sincerely, supposing that they can stir up trouble for me while I am in chains. But what does it matter? The important thing is that in every way, whether from false motives or true, Christ is preached. And because of this, I rejoice” (Philippians 1:15-18).

These people saw Paul as their rival, and they were motivated by a desire to build a name for themselves. They were like the Jewish religious leaders who despised Jesus because they thought his popularity weakened their influence among the people.

Yet, though Paul saw their true motives, he was still glad that the gospel was being preached, since it was the true gospel that they preached.

Is there a role for private correction?

What about the issue of private correction? Is that not the best way to combine the demand for unity and theological faithfulness? To make our linen clean while doing the washing in the bathroom, rather than outside the gate or inside the compound.

Indeed.

Also, this approach caters to the possibility that someone may be teaching heresy or a distorted gospel out of ignorance rather than malice. In that case, a private correction allows them to see their errors and learn from those who are more knowledgeable in a way that public confrontation may not (they may become defensive). Some may see an example of this in the way Priscilla and Aquila treated Apollo (Acts 18:26), though it is most likely this is an error of omission (incomplete truths) rather than commission (truth mixed with errors).

However, such teachers must be willing to admit to their errors to as many people as their errors have reached (which can knowingly or unknowingly include unbelievers on social media). This is in keeping with Paul confronting Peter before all those Peter’s actions Peter influenced. If the preacher privately repents but is not willing to admit his error publicly, then a private correction can be combined with a public one, for the sake of the flock and the integrity of the gospel.

What if a private correction is impossible (due to a lack of access) or unsuccessful? It seems that Paul’s example of calling out heretics and false teachers justifies public naming and confrontation even when a private correction has not been attempted or accomplished.

Nevertheless, where a knowledge of the motives of the teacher is not known (Paul seemed to know this in many cases where he accused them of the desire for financial gain), it is best to stick solely to correcting the teaching to avoid the sin of slander. This also helps in cases where teachers of false teaching are merely ignorant.

The problem with ministries centered on correcting others

Though the protection of the flock is essential, it is inappropriate to build a ministry solely on the correction of others (with “solely” being the key word). Such “discernment” ministries end up fostering divisiveness, pride, and slander, among other vices. This is not a product review podcast or YouTube channel we should be excited about.

The primary calling of church leaders is to proclaim the whole counsel of God and nurture their congregation in the faith.

“The last thing I would say is to let your teaching be so powerful in clarifying the greatness and the beauty and the worth of God’s truth that your people will smell error before it infects their lives,” said Piper. “The shape of error is always changing. You can’t preach enough negative sermons to stay ahead of it. And you don’t have to. The best protection against the darkness of error is the light of truth.”

In other words, a consistent commitment to proclaiming the truth is how you equip your people to identity and stay away from errors. When they know how to identify the genuine currency, they won’t have a hard time identifying counterfeits.

Moreover, the Christian faith goes beyond notitia (knowledge of the content of faith) and includes both assensus (assent to the content of the faith) and fiducia (personal trust and reliance). Christians must constantly drink from the fountain of truth and consistently apply the truth to their lives so they can be progressively conformed to Christ’s image instead of spending all their time identifying the next “heretic.”

[1] Robert Gundry, Commentary on Galatians (Michigan: Baker Publishing Group, 2010), Page 40, Everand.

[2] Don Carson. (2025). Grace and Conflict: Understanding Paul and Peter’s Dispute in Galatians 2. Available at https://www.thegospelcoalition.org/sermon/an-apostolic-disputation-and-justification/

[3] McGrath, Alister E. Heresy: A History of Defending the Truth (p. 40). HarperCollins. Kindle Edition.

[4] Albert Mohler. A Call for Theological Triage and Christian Maturity. Available at https://albertmohler.com/2005/07/12/a-call-for-theological-triage-and-christian-maturity/

[5] John Piper. (2019). Should We Call Out False Teachers or Ignore Them? Available at https://www.desiringgod.org/interviews/should-we-call-out-false-teachers-or-ignore-them