When God is Silent: Seeing Him Who is Invisible

In his book, Enduring Divine Absence[1], Joseph Minch makes the point that the allurement of atheism does not rest only in the intellectual claims of its adherents; instead, he argues that our real challenge is “existential and imaginative – a felt absence of God that is more visceral in our modern world than for most generations past, and the sense that if God cannot be sensed, He cannot be there.”

That is, it is possible to know and believe all the rational arguments for God’s existence (philosophical[2] and scientific[3]) and to still be allured by atheism because of the problem of divine absence.

As Minch argues, this problem arises from the realities of our technological world. In this technological age, we don’t see nature as an agent but as a tool to be used for our own purposes. In ages past, nature was an agent who acted in ways that were existentially significant for people. Through the agency of nature, men could feel the reality of the God who created and orders nature.

But today where we have largely tamed nature, harnessed it for our own good, and have come to accept purely natural explanations for natural realities, it is hard to carve out a space for God. In essence, it is not that we have disproved God as we have made him insignificant to our life. We don’t “see” him so we think he does not exist or at best, he probably created the world in the distant past and left it to run by itself (the deist solution).

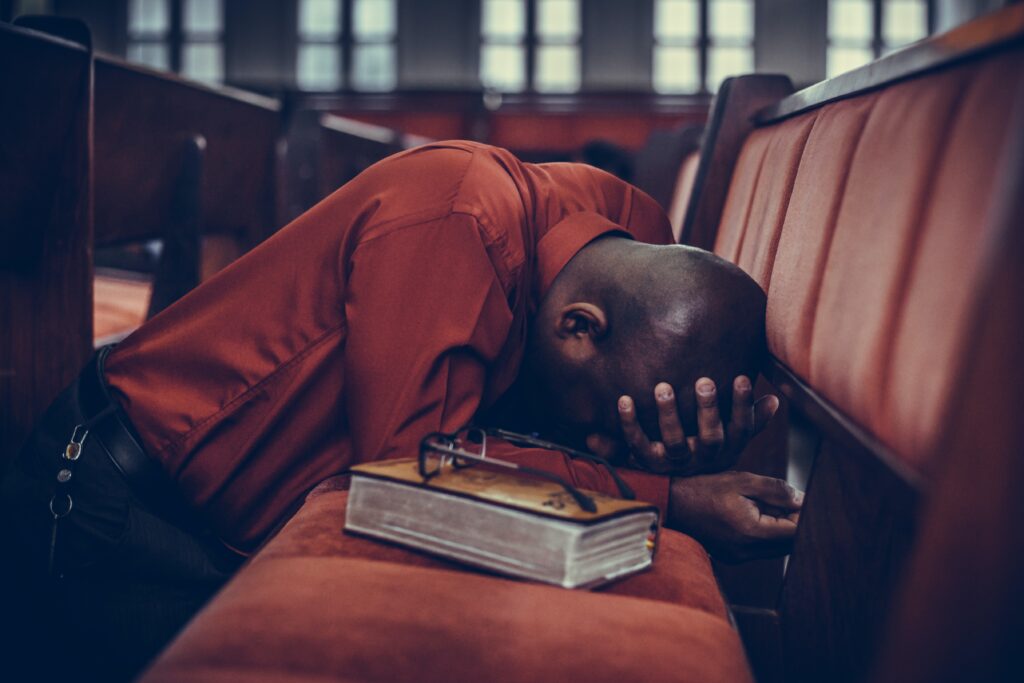

Also, the reality of unanswered prayers and hurtful tragedies deepens this sense of divine absence. When we pray endlessly and answers don’t come and when tragedies befall us, we feel the absence more acutely. In those moments, we may still have strong convictions about the rational arguments for God, but his “absence” makes atheism or deism even more attractive.

How then do we deal with this “existential and imaginative” challenge to our faith? According to Minch, like the Psalmist, we need to cultivate the art of remembrance. “In the moment of crisis and in a context wherein what ‘seems real’ is defined by the immediate, the Psalmist must pause, be still, and re-situate his own immediacy in the context of deeper truths which are both close to the Psalmist objectively and far away from his psychologically.”

God reveals himself to us so we can seek him and the more we seek him, the more we find him. He does not just want us to believe in him (even the demons believe and tremble) but to pant after him. And it is in this panting after him – an act of the will and the affection – that he becomes more real to us.

So, what do we need to remember to reorient our minds and hearts to the reality of God even when he seems absent to us in general or in moments of pain and distress?

God is pure act

For Minch, the first thing to keep on remembering is that God exists and he is “pure being, bliss, plenitude, infinity, greatness, holiness, perfection, love, active and eternal beatitude in the Father, Son and Spirit.”

We, and everything else that exists in the world, are contingent – it could have been otherwise. The universe itself is contingent – it could have been otherwise. And the only reason why a contingent thing or being can exist is the act of the will of another. If the universe is contingent, then it exists by the will of a personal being.

Also, since contingency cannot be infinite, there must be a personal being who exists necessarily and by whose will every contingent thing exists. “All of the incomprehensible vastness of being, the relation of each particular to each particular, obtains because God in His wisdom wanted this world, this universe, these physical laws, this human race, this history.”

So, even though science can explain the material and efficient cause of natural phenomenon, it cannot explain its final cause – why this natural phenomenon exists instead of another; why it has these features and not another; and why it acts in this way or towards this end rather than another.

We might have ignored final cause to stick to material and efficient cause (since those are the ones more important for our technological purposes) but the contingency of nature remains and only the existence of a personal, necessary being can ultimately explain final causes.

This is one of the philosophical arguments for God.

But the more important point here is that we must nurture our minds to remember the philosophical, scientific, and experiential reasons why we believe that God exists.

For most people, the experiential will be more powerful in dealing with the issue of divine absence. Yes, the pain and distress are real at this moment, but what about all those moments when we experienced God’s providence in ways that convinced us that God is? When Asaph was overwhelmed with unanswered prayers and distress, he chose to appeal to “the years when the Most High stretched out his right hand” and remember “the deeds of the LORD,” “the miracles of long ago,” “his mighty deeds” (Psalms 77).[4]

God is for you

Secondly, we need to constantly meditate on the fact that God is for us in Christ Jesus.

This requires that we fix our gaze on the truths of the gospel.

In the gospel, we know that God is good because he has “actually sought to resolve human evil in Himself,” “forgiven my sins,” and he is “remaking the world into His kingdom (ultimately by crowning and purifying this order of things in the new creation – which is just this creation perfected and purified).”

The resurrection of Jesus is the proof that the gospel is true (1 Corinthians 15:17) – that God indeed came into this world, took upon himself our sins, and contended with the evil powers of the world. Christ’s death and resurrection marked the defeat of sin, evil, and death and the inauguration of the new creation.

If God loved us and sent his son to die for our sins (John 3:16) to rescue us from this present evil age (Galatians 1:3), then we can be confident that he will “graciously give us all things” (Romans 8:32). He who has given us the highest gift will give us lesser ones; he who gave his son for our redemption has proven beyond any shadow of death that he is for us.

And the cross and resurrection of Jesus are the ultimate proofs of God’s presence. As Minch puts it, “God has sought us. We have not ascended to heaven; He has descended to earth. Christ is the presence of God to answer all divine absence. ‘Where are you? Where are you? Where are you?’ The answer to this is a cross, a resurrection, a Spirit, forgiven sins, renewed life, and real eternal hope.”

In our grief and distress, as we struggle with divine absence, we must remember that God does not shy away from our pain. He became man and he “learned obedience from what he suffered” (Hebrews 5:8), “suffered when he was tempted” (Hebrews 2:18), and became “obedient to death – even death on a cross.”

Edward Shillito captured this thought in his poem, Jesus of the Scars:

“If we have never sought, we seek Thee now;

Thine eyes burn through the dark, our only stars;

We must have sight of thorn-pricks on Thy brow,

We must have Thee, O Jesus of the Scars.

The heavens frighten us; they are too calm;

In all the universe we have no place.

Our wounds are hurting us; where is the balm?

Lord Jesus, by Thy Scars, we claim Thy grace.

If, when the doors are shut, Thou drawest near,

Only reveal those hands, that side of Thine;

We know to-day what wounds are, have no fear,

Show us Thy Scars, we know the countersign.

The other gods were strong; but Thou wast weak;

They rode, but Thou didst stumble to a throne;

But to our wounds only God’s wounds can speak,

And not a god has wounds, but Thou alone.”[5]

According to Minch, the first point – God is pure act – flows into the second – God is for you. If God is a necessary being, then he didn’t create the world out of any compulsion; this is also called the aseity of God. God created the world as an act of love, the free expression of his love.

Will that God then abandon the world he has made? No! Why not? Because love is an attribute of God (1 John 4:8,16) and God’s attributes are his essence. Therefore, it is impossible for God not to love or to stop loving since love is not what he does but who he is.[6] Consequently, “a God constitutionally unconcerned with man cannot be the God whom we know to be necessary,” said Minch.

We are guilty before God

If Christ’s redemption of the human race is God’s highest display of his love and concern for us – his presence – then it is necessary to continuously meditate on why that redemption was necessary – we are guilty sinners.

We live in rebellion against God and his law (Romans 1). As D.A Carson likes to put it, we de-God God by our idolatrous rebellion against his authority and goodness. Also, it was in man that creation fell and was ruined (Romans 8:18-25) and we continue to contribute to its ruin and chaos.

“It is absolutely urgent that we cultivate the psychological and intellectual capacity to feel this in our bones,” said Minch. “It’s not trivial. It’s a problem. There is a violation that must be dealt with. There is guilt.”

A deep sense of our sinfulness helps us understand why Qoheleth said that God created man perfect but he has sought various inventions (Ecclesiastes 7:29). When we sinned, we not only corrupted our own nature, we dragged down creation with us and that is why we live in a world of spiritual and moral evil.

But a deep sense of sinfulness also helps us to appreciate the goodness of God. As Minch puts it, “many gods have exercised mercy. But here God forgives His enemies by sheer grace, not by ignoring the enormity of their crime, but by drinking His own righteous judgment in the Person of Christ to the very last drop.”

Trusting God

In his book, Trusting God[7], Jerry Bridges also emphasises that the only way we can deal with divine absence is to keep contemplating the realities of who God is. There are three points he made:

God is sovereign

In essence, God is in control of the world he made and preserves. The knowledge of God’s sovereignty helps us understand that nothing happens to us outside of his good purposes. Through his providence, he constantly cares for and rules over creation “for his own glory and the good of his people.”

God’s sovereignty means that first, nothing happens to us by mere chance or fortuitousness. Therefore, even in those ugly moments when we feel God is absent, he is actually present. When Job was suffering, it seemed to him that God was nowhere to be found. But those of us reading the text know that God was sovereign over his suffering and that he was present all through, as the latter chapters made evident.

Second, it means that all good things come from him (James 1:27). Yes, there are secondary causes through whom/which God pours out his blessings, but at the head of all them is the sovereign God, the ultimate final cause, the only necessary being through whom all contingent beings/things exist. Unbelievers who live as if God is absent and creation is self-causing and self-sustaining are unthankful people (Romans 1:21) who are more concerned about using/manipulating creation for their purposes rather than glorifying the God without whose will nothing will exist.

God is wise

“‘For my thoughts are not your thoughts, neither are your ways my ways,’ declares the LORD. ‘As the heavens are higher than the earth, so are my ways’” (Isaiah 55:8-9).

Most times we find it difficult to fathom why God does what he does. His providence looks strange to us; this is why we always ask ‘why’ as an expression of our inability to wrap our heads around his sovereign disposition.

But “God does know what he is doing,” said Bridges. “God is infinite in His wisdom. He always knows what is best for us and what is the best way to bring about the result.” We can therefore be confident that he is working out all things for his glory and for our good (Romans 11:36; 8:28).

For example, he designs our trials for our holiness and righteousness (Hebrews 12:7-11) so that we can be mature, complete, and not lacking anything (James 1:4).[8] As Bridges put it, “God’s infinite wisdom then is displayed in bringing good out of evil, beauty out of ashes. It is displayed in turning all the forces of evil that rage against His children into good for them.”

“Oh, the depth of the riches of the wisdom and knowledge of God! How unsearchable his judgments, and his paths beyond tracing out” (Romans 11:33)!

God is love

“Just as it is impossible in the very nature of God for Him to be anything but perfectly holy, so it is impossible for Him to be anything but perfectly good,” said Bridges.

Also, “there is no doubt that the most convincing evidence of God’s love in all of Scripture is His giving His Son to die for our sins.” Bridges continues, “calvary is the one objective, absolute, irrefutable proof of God’s love for us.”

The sovereignty, wisdom, and love of God show us that he is indeed present – as creator, sustainer, and redeemer. As Minch said, what we need is to keep remembering these truths and dwelling on them personally and corporately. That is, we must cultivate our minds to think God’s thoughts after him. This is the only way we will avoid joining the ranks of the unthankful, who receive God’s good gifts but are blind to the giver because they are consumed with manipulating the gift, or those who in their grief see nothing but the evil of nature and man.

Seeing him who is invisible

“Though you have not seen him, you love him; and even though you do not see him now, you believe in him and are filled with an inexpressible and glorious joy” (1 Peter 1:8).

While the modern world wants to “force” us to believe that only that which is visible and manipulable is real, believers are those who, like Moses, see the invisible (Hebrews 11:27). We don’t see God but we know that he exists – he is pure act, necessary being – he is for us – the cross and the resurrection of Jesus being the ultimate proof – and that we are guilty before him – as our conscience, the fallenness of creation, and the cross of Christ reveal.

And, as said before, the more we seek him, which is the goal of God’s revelation of himself to us, the more we come to know him. He is still invisible, but the more we seek him, the more we come to know his presence. Our souls, like that of the Psalmist, must follow hard after him (Psalms 63:8).

And the more we find him, the more of him we seek. As AW Tozer puts it, “To have found God and still to pursue Him is the soul’s paradox of love, scorned indeed by the too-easily-satisfied religionist, but justified in happy experience by the children of the burning heart.”[9]

It is to this pursuit that we must devote ourselves. If the world continues to loom large on our horizon and we do not seek God, we will become more embroiled in its mechanistic view of creation. The only solution is for us to regularly feast on God and draw near to him even as he draws near to us.

I hunger and I thirst:

Jesu, my manna be;

ye living waters, burst

out of the rock for me.

Thou bruised and broken Bread,

my life-long wants supply;

as living souls are fed,

O feed me, or I die.

Thou true life-giving Vine,

let me thy sweetness prove;

renew my life with thine,

refresh my soul with love.

Rough paths my feet have trod

since first their course began:

feed me, thou Bread of God;

help me, thou Son of Man.

For still the desert lies

my thirsting soul before:

O living waters, rise

within me evermore.[10]

Footnotes

[1] Joseph Minch, Enduring Divine Absence (Moscow, ID: Davenant Institute, 2018).

[2] Edward Feser, Five Proofs of The Existence of God (San Fransisco: Ignatius Press, 2017).

[3] Stephen Meyer, Return of the God Hypothesis (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2021).

[4] For more on this, see The Renewed Mind, Remembrance: The Cure For Discontent And Anxiety, Available at: https://renewingthemind.org/the-cure-for-discontent-and-anxiety/

[5] Edward Shillito, Jesus of the Scars. Available at: “Jesus of the Scars” (thegospelcoalition.org)

[6] See Matthew Barrett, None Greater: The Undomesticated Attributes of God (Michigan: Baker Publishing Group, 2019).

[7] Jerry Bridges, Trusting God, 2nd edition (Colorado Springs: NavPress, 2008).

[8] See The Renewed Mind, Suffering and Sanctification: How God Purifies Us Through Our Trials. Available at: https://renewingthemind.org/suffering-and-sanctification/

[9] AW Tozer, The Pursuit of God: A 31-Day Experience (Kaduna: Evangel Publishers, 1995).

[10] John Monsell, I Hunger and I Thirst in Hymns Ancient and Modern (London: University Press), Hymn #413.